What happens to hidden tears?

Posted: December 6, 2023 Filed under: Current Exhibition, Uncategorized | Tags: art, Contemporary Art, mixed media, Placeholder, stamp gallery, UMD, University of Maryland Leave a commentPlaceholder from October 10 to December 9, 2023 at The Stamp Gallery | University of Maryland, College Park | Written by Reshma Jasmin

In the past few years, I’ve been making a concerted effort to cry.

“Men don’t cry” is society’s mantra for masculinity. Emotions are seen as weakness, and men are meant to be strong, so crying, which is an overflow of emotions, is emasculating. Even though I was not socialized as a man, I still learned that tears equal weakness when I was pretty young, and I was quick to internalize it. Starting when I was seven or eight, I would hide whenever I was upset— in various closets, under my bed, under desks, in between and behind furniture. My tears were meant to be hidden too, but I was never allowed to remain hidden, and neither were my tears as my brother and parents would immediately search and pull me away from my too fleeting enclosed sanctuary.

After a traumatic experience at age nine or ten, I was more adamant about hiding. I still cried, but my sobs were suppressed, so I never made a sound. I would hold shut the doors of the various closets when someone found me. In my arguments with my family, or when feeling overwhelmed in some way, tears would well up in my eyes, but I never let them fall in front of people. When I was eleven, I learned that what I’d gone through was traumatic, and until I was seventeen, I didn’t cry at all. My eyes only ever welled up because of seasonal allergies.

When I first walked through Placeholder, I saw some of my struggle reflected back at me in the pieces by artist James Williams II.

Williams is an American artist based in Baltimore, MD whose work focuses on aspects of racial constructs, systemic racism, and cultural identity. In his artist statement, he explains that his work is meant “to challenge the ambiguity of the Black construct as both an object and personhood.” His pieces in Placeholder explore the hidden nature of identity and emotion in the Black experience. Williams explains that his work as an artist and professor is inspired by his older daughter’s questions about race. He tries to simplify the Black construct because even with all the complexity ingrained in race in America, he believes “it’s not as complex as we make it.” (from the artist’s website). He embodies “a childlike understanding” of experiences and perceptions of Blackness in America by using a blend of multiple mediums.

In the artists panel during the opening reception of Placeholder, he recounts the moment his daughter said, “I don’t see you cry.” Williams responded that he has cried, especially thinking back to his experiences as a young Black boy in upstate New York, but his daughter’s observation appears to have stuck with him.

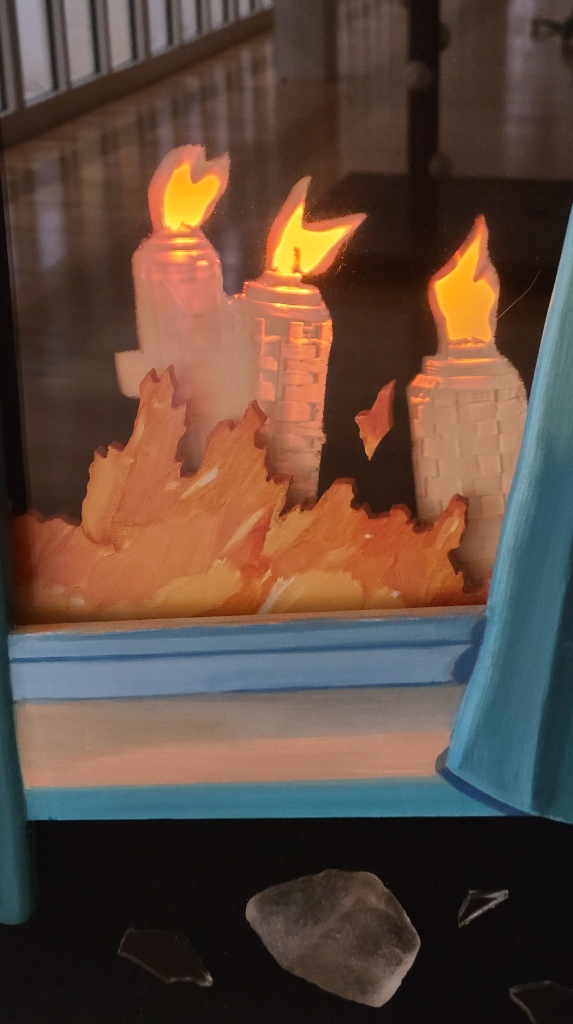

The socialized stigma of crying and vulnerability is especially prevalent in Black communities. Due to systemic and societal/cultural racism in America, Black people are forced to be resilient just by existing. In an effort to maintain the image of being strong and avoid losing resolve, Black people are socialized to suppress their emotions and hide their tears. The title This Ski Mask is for Hiding Tears suggests that the ski mask is a refuge from being seen in weakness. The identity of the wearer is obscured, since they are not seen as an individual but as a “Black person”— a generalized entity that embodies all the stereotypes of Blackness. A ski mask is also a symbol of the racist perception of Black people as criminals. The ski mask objectifies its wearer by stripping personhood and replacing it with a criminal status. Ultimately, the tears are the only things that are visible above the mask, but they still go unseen because people do not sympathize with perceived criminals.

When reading the title Calm Before, our minds automatically add in “the storm” to finish the phrase. The phrase refers to the quiet period before disaster strikes, and explains the anxiety that comes when things are too quiet or go too smoothly. Pressure builds when confined, so the “calm before” is really the roller coaster going up its first hill— the higher it goes, the more intense the drop.

The title Calm Before suggests a work that would depict that foreboding period of stillness when the storm clouds are forming. But the piece depicts a chaotic storm with teardrop rain falling from an angry cloud in a dark woods. The drops are different colors, sizes, and mediums— oil paint on canvas, paint on panel, or velcro. Unlike the more common titles that summarize the content of a piece, Calm Before is like the title of a poem that also serves as the first line. The title is followed by the piece, which illustrates “the storm.” This also captures that the calm before and the storm after are the same— the chaos and pain just move from internal to external. Or there is no storm at all, and it stays confined in the calm before, tears that build up never fall, and the pressure builds with no release. Either interpretation simplifies the building emotions that Black Americans carry throughout their entire “calm” or “normal” lives due to the nature of racism in America.

I encountered my own storm when I was seventeen. The bottle holding everything I refused to feel or confront for years exploded, and I sobbed unceasingly— still silent, but uncontrollable. Unfortunately, I quickly returned to a state of calmness where my tears would at least well up with emotion, but I could never find release by crying, even when I was alone.

Williams’s work does not resonate with me in the same way it would for a Black viewer. He captures the complexities of handling and expressing emotions that Black people encounter due to the societal realities of racism and racial constructs in America. The Black experience he illustrates comes from his own lived experience. To me, Williams’s work is heart-wrenching and beautiful. His pieces tell me that tears will stay hidden and the storm will remain trapped in the calm before; that is the natural state of things, as he has experienced. But he shares that pain with the world through his work, so his pain becomes visible. Though it seems somewhat bleak and scary, his vulnerability is his strength. And that makes me want to continue making an effort to cry.

James Williams II’s works are included in Placeholder at The Stamp Gallery of the University of Maryland, College Park, from October 10 to December 9, 2023.

For more information on James Williams II, visit https://www.jameswilliamsii.com/.

For more information on Placeholder and related events, visit https://stamp.umd.edu/centers/stamp_gallery.

Saving Space: When Placeholders Are Not Enough

Posted: November 30, 2023 Filed under: Current Exhibition | Tags: Critical Consciousness, Danni O'Brien, Isabella Chilcoat, James Williams II, Placeholder, saving space Leave a commentPlaceholder from October 10 to December 9, 2023 at The Stamp Gallery | University of Maryland, College Park | Written by IsabellA Chilcoat

I spent ten days in Austria at the beginning of October. Worth it? Yes. Still facing the consequences for my coursework a month later? Also yes. But I’d do it again. In accordance with my art historian heart, I visited as many art museums in Vienna as I could squeeze into my packed travel itinerary. At every museum, I was the tourist b-lining to the gift shop for another over-priced, poorly constructed canvas tote bag (treasure) in the gift shop. Also worth it.

I returned to the U.S. (with a suitcase full of tote bags) just in time for the Stamp Gallery’s exhibition Placeholder – wishing I had a personal placeholder while I was away who could have done my make-up work for me.

I define “placeholder” as a thing that stands in for something else, like a substitute or that blank line waiting for your signature on a piece of paper.

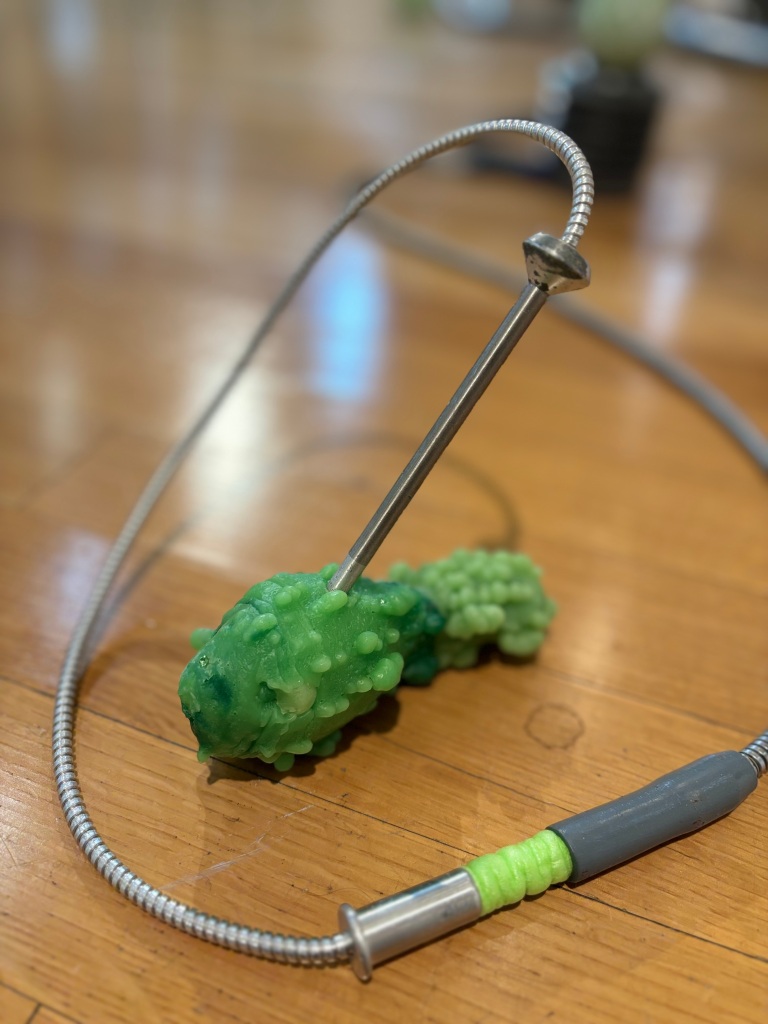

This is similar to Danni O’Brien’s entanglement of wax gourds that represent a kind of humanoid organic matter within the technical and metallic hardware of their sculptures. Wax gourds act as a placeholder for human flesh or truly organic matter. We can also observe the idea of a placeholder at work in how James Williams II invokes the story of Frankenstein’s monster in God Don’t Like Ugly (2022) to draw parallels with aspects of the racialization and violence imposed on Black people throughout U.S. history without being so explicit in his imagery. Placeholders like these help us to explore familiar things in a new light, or they can remove certain barriers so that we might better understand or relate to a message.

Rather than taking an artwork at surface value, recognize art as keeper of many truths, placeholder of its many beings.

While artworks may have placeholders within them to suggest issues or ideas, art can also be the placeholder for broader contextual moments in time or in the maker’s life. Artwork can be the placeholder for an artist’s own thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Or art can become a placeholder for the viewer’s own memory. As an object ages, it assumes a history of its own which renders the work a marker for associated moments and memories. When I look at the wrinkled museum bags in my closet, my memory awakens. When I strap one over my shoulder to leave the house, I imagine that the tote carries more than just my phone, wallet, keys, and chapstick.

Sometimes, however, placeholders alone are insufficient. When an accepted narrative about people, politics, and the world around us is fabricated around partial truths pieced together to fit the most convenient conclusion for the time, a placeholder is not only insufficient, it is false. This begs the question, when does a placeholder become all we know about a particular topic? At what point in time does the completeness of an experience, event, or truth disappear? My tote bags are never going to capture the entirety of my Viennese experience, my encounter with Gustav Klimt’s sparkling Beethoven Frieze at Secession or the aroma of strudel from the cafe next to my hotel.

When we encounter placeholders, it is essential to examine and re-examine the material, to never neglect raising a critical consciousness. Accordingly, imagine what lies beyond the forms you might see represented on an artwork’s surface. Engage with the critical context that influenced the maker, and then yourself, the viewer. What did/does the artwork inspire? How many merging histories, thoughts, and emotions reside in one piece of visible history? Rather than taking an artwork at surface value, recognize art as keeper of many truths, placeholder of its many beings.

…

Danni O’Brien and James Williams II’s works are included in Placeholder at The Stamp Gallery of the University of Maryland, College Park, from October 10 to December 9, 2023.

For more information on Danni O’Brien, visit http://www.danielleobrienart.com/.

For more information on James Williams II, visit https://www.jameswilliamsii.com/.

For more information on Placeholder and related events, visit https://stamp.umd.edu/centers/stamp_gallery.

Adapting Art in Changing Times

Posted: October 31, 2023 Filed under: Current Exhibition, Uncategorized | Tags: Contemporary Art, exhibition, gallery, Placeholder, Richard Hart, stamp gallery Leave a commentPlaceholder from October 10 to December 9, 2023 at The Stamp Gallery | University of Maryland, College Park | Written by Rachel Schmid-James

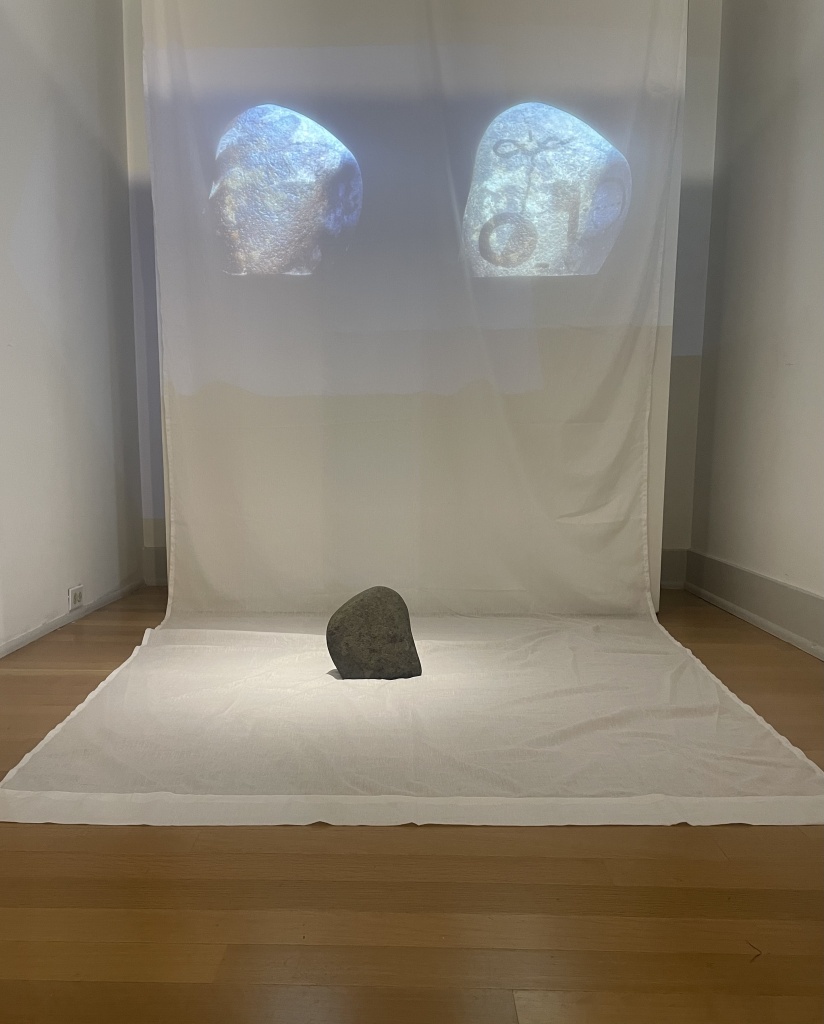

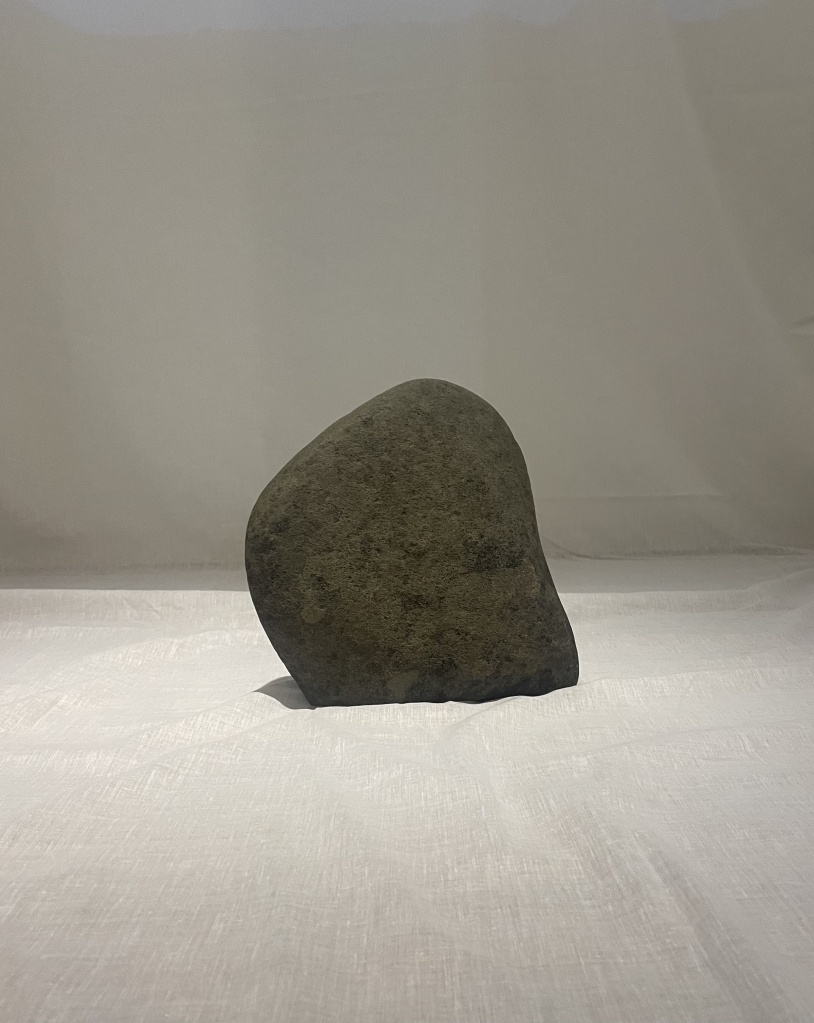

In an age of rapid growth and change on Earth, it can be difficult to keep up. With Artificial Intelligence becoming smarter and robots becoming more and more a part of everyday life, we can either choose to succumb to the fear of losing everything to this up and coming technology, or utilize them to enhance and move forward. For many artists, electronics have become a useful tool in creating new, experimental pieces that before would not have even been possible. Such is the case with one of artist Richard Hart’s most recent pieces. Hart, whose past works have often focused around political issues and life in his native South Africa, decided to explore an idea using a new medium: rocks. Double Water Drawing (Croton River Rock) combines both the natural world and technology, as well as the physical and the untouchable.

On a blank, white, unstretched canvas, a singular rock (from Croton River in southern New York as the name suggests) stands smack down the middle, upright and rigid. Above and behind it, a projection of two other rocks is visible. Each rock is continuously “painted” with water, which then evaporates before a new design is created. No hand is shown creating these markings, and the video is clearly sped up as the drying process between each one takes mere seconds. The work is partially based on the concept of impermanence. Nothing is forever, the same way that the water designs on the rock will at some point dry and disappear. However, I think this message goes deeper than just the rocks. The use of technology in this piece, in a way, represents the impermanence of our constantly changing world, especially as the “old ways” of doing tasks in many careers are disappearing the same way the water fades from a rock.

Hart’s work seems to ask us: how do we come to terms with the idea of constant change and evolution, while also not allowing it to take over our lives? We live in a time when artists working across all media fear AI taking their jobs or stealing their work for its algorithm. Billions of people have the world at their fingertips through the internet. Long gone are the days of classic art only being seen in museums. How do we move forward? Hart and other artists answer through pieces like Double Water Drawing (Croton River Rock): we embrace it and find a way to meld it into our art. The projector and the video add a layer to the work, enhancing instead of inhibiting. These changes can be tools if only we are able to accept them.

However, the future of AI taking over art is, I think, an unlikely one. Art is something so distinctly human, something we have been doing long before modern Homo Sapiens existed. When humans lived in caves they created swirls and illustrations using their hands and natural pigments, even lifting their children up to the ceiling so they could be a part of the ritual. It is this concept that I see reflected in Hart’s piece. The painting of rocks using water is something familiar, an activity that my friends and I used to do when we would play at the creek near my house—always disappointed when our creations would fade away in the hot sun. The combination of the old and the new in Double Water Drawing (Croton River Rock) gives me hope that art can continue on even when things feel uncertain, and that new technology does not need to be our enemy.

Richard Hart’s work is included in Placeholder at The Stamp Gallery of the University of Maryland, College Park, from October 10 to December 9, 2023. For more information on Richard Hart, visit https://www.richard-hart-studio.com/. For more information on Placeholder and related events at The Stamp Gallery, visit https://stamp.umd.edu/centers/stamp_gallery.

Unfolding Doughtie’s Concepts Behind Placeholder

Posted: October 24, 2023 Filed under: Current Exhibition | Tags: Contemporary Art, Elliot Doughtie, exhibition, gallery, Placeholder, sculpture, stamp gallery Leave a commentPlaceholder from October 10 to December 9, 2023 at The Stamp Gallery | University of Maryland, College Park | Written by Ellen Zhang

The Stamp Gallery’s newest exhibition Placeholder pays homage to the power of materials and images in their ability to contrast absence and presence, permanence and impermanence. Four artists (Elliot Doughtie, Richard Hart, Danni O’Brien, and James Williams II) have manifested these concepts into works of art that represent their individual interpretations. For those that keep up with the Stamp Gallery’s exhibitions, you may remember Elliot Doughtie from his iconic piece, Laundry Day Dubuffet, as part of the Gallery’s Spring 2023 exhibition UNFOLD. This time around, Doughtie has opted for fruits, instead of socks, as his muse.

As the name suggests, Orange features a collection of partial oranges arranged on a pole. Each orange looks like it has been sliced at a series of odd angles and curves, creating the illusion that the oranges are sprouting out of the pole. What I find intriguing about Doughtie’s work is his ability to play with structure and shape in order to create illusion. In Laundry Day Dubufffet, Doughtie arbitrarily stacks sock replicas, made out of plaster, leaving the viewer confused as to how this work is able to stand on its own. In Orange, the artist also utilizes plaster to mold the shape of partial oranges into the sides of the pole. While it is unclear how these oranges are able to stick to the pole, it creates the perception of oranges growing out of a pole.

This visual effect raises the question of permanence versus impermanence: Is this body of work permanently “done”? Will these partial oranges grow into whole oranges? By using fruit as his medium, Doughtie cleverly pokes at the idea of continuous growth. As an organic fruit grows, it undergoes various stages of development until it fully matures and detaches from its source. In Orange, I interpret the pole as the “source,” providing the necessary nutrients for each orange’s growth. Given that the partial oranges have not fully developed, we as the viewers are seeing a snapshot of something “in progress.”

In addition to permanence versus impermanence, Doughtie alludes to absence versus presence. Upon a closer look, you will notice that the base of Orange has holes with imprints of an orange. This is evidence of a ripe orange that has dropped from its source, yet the orange itself is nowhere to be seen. As a viewer, we are seeing evidence of the full life cycle of an organic orange, from its “in progress” phase to evidence of its maturity. In a way, the sculpture reflects a kind of dynamic life on its own. Through this, Doughtie also simultaneously invokes absence and presence. In this case, we are aware of the existence of something, but its physical presence remains hidden from view. Perhaps, Doughtie will add the ripe orange later on, thus indicating the imprinted hole as a placeholder for the ripe orange.

The concepts of permanence versus impermanence and absence versus presence are more than abstract notions. They manifest into individual thoughts, experiences, and emotions. For many students, permanence and perpetuity are sources of fear. They fear making choices due to the anxiety of making the wrong decision and becoming trapped with the consequences of that choice. In my own life, I have also experienced how absence and presence interact with one another. As Doughtie shows the presence of an orange through its absence, I can’t help but think of the well-worn cliche of “you don’t know what you have until it’s gone.” However, it doesn’t seem so cliche when I think back on my friendships that have come and gone; I have been forgetful in appreciating present relationships until they have faded away.

While some may think Placeholder as a purely abstract exhibition, the themes that the artists convey certainly permeate into the real world. I particularly enjoy how Doughtie experiments with structure and shape to craft the viewer’s perceptions in a way that enhances the message he is communicating. From Laundry Day Dubuffet to Orange, he continuously challenges conventions surrounding form and composition to express nuanced yet relatable concepts.

Doughtie’s work is included in Placeholder at The Stamp Gallery of the University of Maryland, College Park, from October 10 to December 9, 2023. For more information on Elliot Doughtie, visit https://elliotdoughtie.com/. For more information on Placeholder and related events at The Stamp Gallery, visit https://stamp.umd.edu/centers/stamp_gallery.